Blog

Getting Redis Modules Into ARM Land – Part 1

Here at Redis, our motivation to bring Redis modules into ARM land was RedisEdge. Redis, of course, has long been native in this land, in both glibc and alpine/musl variants. Redis modules have already been on the multi-platform scene, running on various Linux distributions and supporting macOS mainly for the sake of development experience. However, it was more enterprise/data-center-oriented until RedisEdge, which targets IoT devices. In this series of posts, I’ll describe our vision of ARM platform support and the developer user experience, as well as the steps we took to get there.

If you follow along, you’ll end up with a fully functional ARM build laboratory.

Inside RedisEdge

Let’s take a look at RedisEdge. RedisEdge is not a Redis module but an aggregate of three Redis modules: RedisGears, RedisAI, and RedisTimeSeries. It is distributed as a Docker image, which is based on Redis Server 5.0. Thus, one can simply pull the image, run it, and start issuing Redis commands; load models into RedisAI; and execute Python gears scripts on RedisGears. Although one can easily remove Docker from the equation by installing a Redis server and copying Redis modules files, we’ll see that Docker actually provides significant added value and is worthwhile to keep.

Inside RedisEdge: modules structure

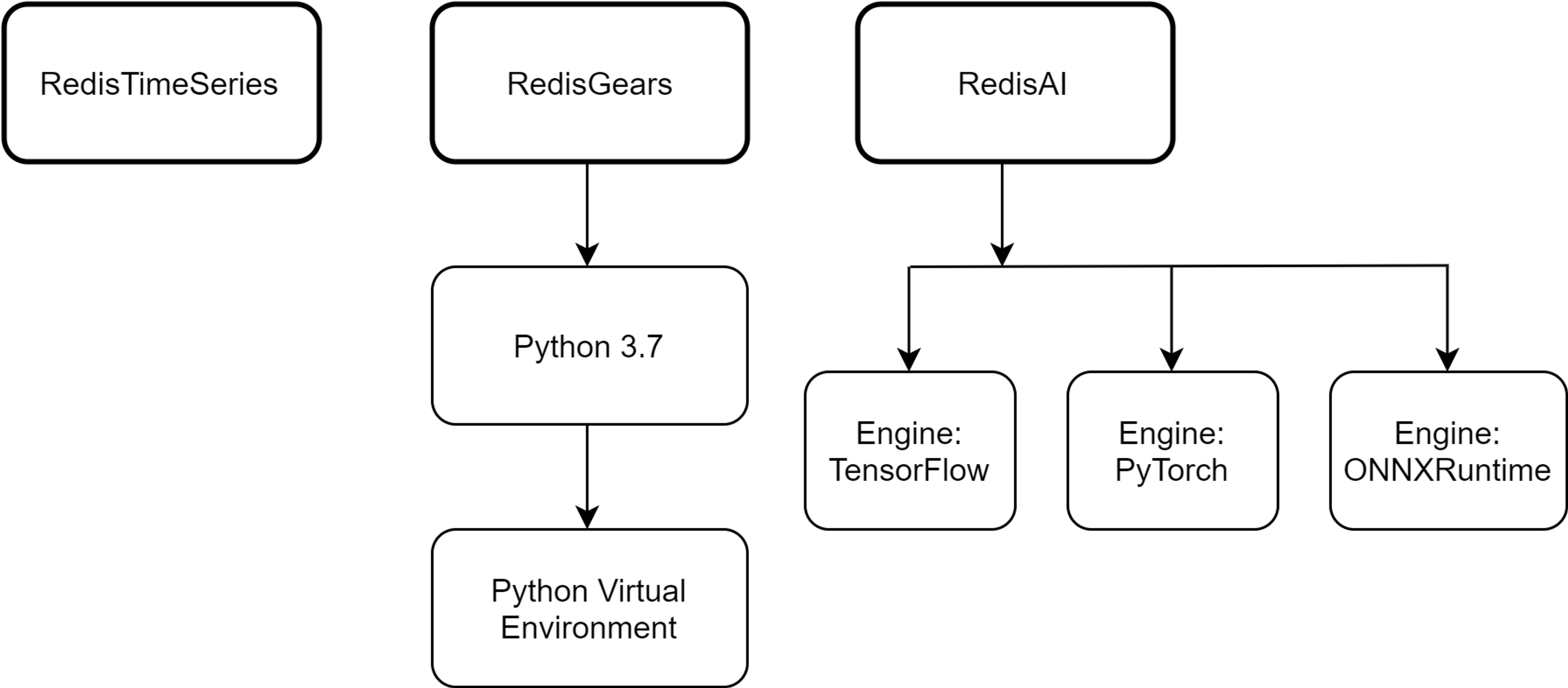

Let’s now take a look at each component of RedisEdge to figure out what would it take to have them ported to ARM. First, RedisTimeSeries. It’s a simple C library built with make. Not even a configure script. No problems there. Next is RedisGears. It’s a C library built with plain make, and it also uses an embedded Python 3.7 interpreter, which is built from source. This requires running automake to generate a platform-specific makefile. Finally, RedisAI. It’s a C library built with CMake, and it includes modular “engines” that allow abstraction and encapsulation of AI libraries like TensorFlow, PyTorch, and ONNXRuntime, in their C library form—most users typically use them in Python, with PyTorch and ONNXRuntime not officially supporting ARM. So the build requirements, as it seems, have deteriorated quickly. It went from building an innocent C library to compiling massive source bases with convoluted build systems.

In the following sections, we will fit each component with its proper build method.

Building for ARM

At this point, we’ll pause and take stock of what is required to build software for ARM. The obvious way is to use an ARM-based device, like Raspberry Pi. Once set up, you’ll be able to build and test in the most natural manner.

The testing medium is important: even though you can build almost every ARM software without a physical ARM device, there is no way to reliably test the outcome without such a device, especially with non-standard devices. Therefore, while a virtualized/emulated/containerized test may be useful, you should always test your software on its designated target device.

A Raspberry Pi 4 with 4GB RAM (and a 1Gbps NIC, no less important) and a fast microSD card look promising.

Regarding the OS selection on ARM: the offerings are limited, and the rule of thumb is to go for the latest release of Raspbian (which is customized Debian distribution for RPi), Ubuntu, or Fedora, the latter two offering easy-to-install ARM systems. Do not worry about immaturity: it was proven time and again that newer systems work better and old ones can’t keep up.

Installing an OS brings us to the first dilemma: If we install Raspbian, we get a 32-bit OS (i.e., arm32v7 platform). If we choose 64-bit Ubuntu, we get an arm64v8 platform (we discuss ARM platforms in detail later). If we intend to support both platforms (as we do with RedisEdge), we can either get two SD cards and install each OS on its own card while taking turns on the device or get two RPi devices (which is not terribly expensive). I recommend the latter.

And now, for the principal principle of OS selection: our goal is to have a stable system with the newest Docker version. Any OS that will satisfy these requirements will do. That’s right: we’re going to use Docker to fetch the OS we really wish to build for, using the underlying OS as infrastructure. This will also help keep our build experiments properly isolated.

If you have an RPi device at your disposal, you can now proceed with making it functional. In the next post, we will present build methods that do not require a physical ARM machine.

Installing Ubuntu 19.04 on RPi 3 & 4

Very good and detailed instructions on how to download and install the latest Ubuntu Server for ARM on RPi can be found here for Linux, Windows, and macOS. However, you should follow the following instructions to install Ubuntu 19.04 rather than the latest released version:

- Get a microSD Card: 64GB, Class 10, anything comparable (that is, at the same price level) to Samsung EVO or SanDisk Ultra will do.

- Download the OS image (typically .img or .raw format, archived) and extract it. While it is possible to install from an .iso file, using .img images is much more straightforward and therefore recommended.

- Write it to a microSD card with a tool like Balena Etcher (it’s available for all platforms, I personally use Win32 Disk Imager). In order to write, you should use the built-in microSD reader in your laptop or get an external one with a USB interface.

- Insert the microSD into the RPi and power the device on.

- Username/password: ubuntu/ubuntu

Installing Raspbian Buster on RPi 3 & 4

- Repeat the above steps with Raspbian Lite image.

- Username/password: pi/raspberry

Connecting to workstation

By “workstation,” I’m referring to a Linux or macOS host that holds one’s development environment and git repositories. As a side note, I highly recommend using a desktop PC (that’s another blog post), though most people use laptops. In either case, I also recommend having some virtualization infrastructure on your workstation, such as VMware Workstation/Fusion or VirtualBox.

So, we need to establish a network connection between the RPi and the workstation. As mentioned before, RPi 4 has a 1Gbps NIC, which is a great improvement over the RPi 3 with its 100Mbps NIC. Connecting the RPi to a network is simple: get any gigabit Ethernet unmanaged switch and two Ethernet cables, then hook the RPi to the switch and connect the switch to your gateway Ethernet port. You can hook your workstation to the switch as well.

At this stage, we need to gather some information from the workstation.

First, we need to determine UID & GID of the workstation user that owns the views:

We’ll call them MY-UID & MY-GID.

Next, we need to find out what’s our time zone:

We’ll call it MY-TIMEZONE.

Finally, we’ll need your workstation’s IP:

We’ll call is MY-WORKSTATION-IP.

RPi configuration

During the initial setup, you’ll need to have the RPi connected to a monitor and a keyboard. Once setup is complete, it can be controlled from your workstation via SSH.

Another good practice is to avoid cloning source code into the RPi, instead sharing it between your workstation and RPi via NFS.

For convenience, I assume we operate as root (via sudo bash, for instance).

So let’s get on with the configuration:

Hostname

Time zone and NTP

SSH server

IP

NFS client

Add the following to etc/hosts:

Also, add the following line to etc/fstab:

Utilities

On the workstation side

Regarding git repositories, I’ll use the following terminology and structure throughout the discussion. This is not essential and one may organize matters differently. The term “view” refers to a set of git repository clones that one uses in a certain context. For instance, if we work on RedisEdge modules in the context of ARM compilation, we’ll end up with the following directory structure:

Here ‘arm1’ is the view name, and the directories it contains are the result of the corresponding git clone commands. There may be other views serving other contexts. The idea is to share this structure among all hosts and containers to avoid the hassle of moving code around and git key management.

For even more convenience, I add the following link:

So, finally, we get to set up NFS.

Now proceed as root:

Ununtu/Debian:

Note the MY-UID and MY-GID values.

Fedora/CentOS:

Note the MY-UID and MY-GID values.

Note that if you’ve got your workstation firewall enabled, it might interfere with NFS. Consider turning it off for wired connections.

Back to the RPi

Now that we have NFS set up on the workstation, we can mount the views directory into the RPi:

Finally, we can install Docker and Docker Compose.

Installing Docker on Ubuntu 19.04:

Installing Docker on Raspbian Buster:

In the next chapters

In the next post, I’ll present the developer experience we’re aiming for, discuss ARM platforms in detail, present methods for building for ARM without using ARM hardware, and start putting theory into practice with RedisEdge modules.

Stay tuned!

Get started with Redis today

Speak to a Redis expert and learn more about enterprise-grade Redis today.